Review: 'The Painted Bird' wallows in the misery of a boy's hard road, in which the Holocaust is just one more pothole

What’s the opposite of a “feel-good movie”? Whatever the term is, director-screenwriter Václav Marhoul’s “The Painted Bird” is that: A painfully self-regarding wallow through the darker aspects of humanity.

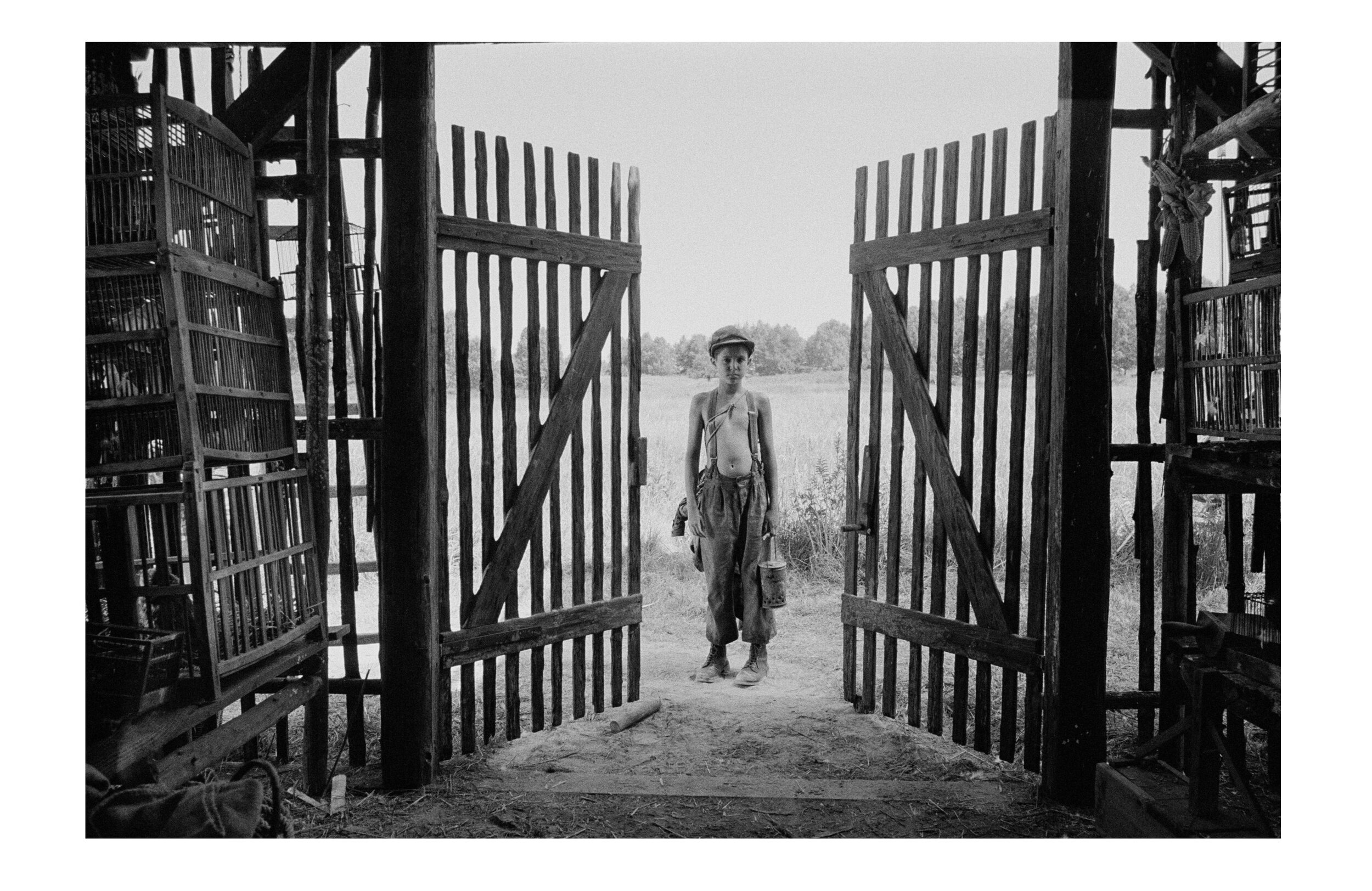

Adapting Polish author Jerzy Kozinski’s then-controversial 1965 novel, Marhoul begins in an unnamed eastern European country with a boy (Petr Kotlár) whose name is not immediately disclosed. The boy has been left by his parents in the care of an aged peasant aunt, Marta (Nina Shunevych), on a farm. The era, from available evidence at the beginning, could be anywhere from 1700 to 1950.

With scant information, Marhoul invites us to witness the boy’s struggles after Marta dies and he must venture out on his own. At the first village, he’s branded a gypsy or a warlock, and the town’s mystic, Olga (Alla Sokolova), makes the boy her servant. The boy eventually breaks free of this bondage, only to be treated even worse in the next village, where he becomes the servant of a miller (Udo Kier), who gets violent when he realizes his hired hand (Zdenek Pecha) lusts after the miller’s wife (Michaela Dolezalová).

And so it goes at the boy’s next stop, and the next. At a few locations, the boy sees two symbols that pinpoint the timeframe. One is the hammer and sickle, on the cap of a cruel Soviet military man. The other is the swastika, flying over the building where German soldiers are headquartered.

Yes, as bad as you thought the boy’s life already was, now you know it’s going to get worse — because, if you didn’t know the history of Kosinski’s book, you’re now learning that we’re in the middle of a Holocaust movie.

Up to this point, we have watched this boy suffer various manifestations of cruelty and barbarity. Now, we’re confronted with the most cruel, most barbaric action in modern history — the systematic, industrialized extermination of millions of human beings — and it becomes just one more bad thing that happens to this kid.

What’s more, one of the few times someone is nice to him, it’s a German soldier (Stellan Skarsgard) who’s ordered to take the boy down the railroad tracks and kill him — but, instead, the soldier lets the boy escape, firing his rifle to make the others think he’s completed the task.

Such good luck is short-lived. Even the kindness of a village priest (Harvey Keitel, his Czech dialogue dubbed over), who sends the boy to live with a parishioner (Julian Sands), becomes hollow when we learn the parishioner is a pedophile.

The question at the heart of “The Painted Bird” is not whether the boy will survive the war — that seems inevitable, both because of his talent to adapt to his circumstances and because of the screenwriter’s trick that we’re going to follow this kid to the bitter end. The question becomes whether the boy’s soul can be preserved, or whether exposure to so much nastiness will leave a permanent stain on his heart.

The answer, alas, is as bleak as Marhoul’s plodding pace and cinematographer Vladimir Smutny’s grimly poetic images. At the end of the movie’s nearly three-hour run, a viewer may be left feeling much as critics did when Kosinski’s book was first published: Pummeled into sadness by a story that exploits the Holocaust for the artist’s own nihilistic purposes.

——

‘The Painted Bird’

★1/2

Available Friday, July 17, for rental on most digital platforms. Not rated, but probably R for strong sexuality, nudity, strong violence and language. Running time: 169 minutes; in Czech, German, Russian and Latin, with subtitles.